Honouring the History of Square Dancing in Australia

This space is dedicated to preserving and celebrating the legacy of square dancing across Australia.

We’re gathering club histories, memorabilia, photos, recordings, videos, and stories of the dancers and callers whose contributions deserve to be remembered.

If you have items or information, you’d be happy to share, we’d love to hear from you.

Whether it’s a treasured snapshot, a vintage program, or a tribute to someone who helped shape the square dance community, your contribution will help future generations appreciate our history.

Copyright and Permissions

We’ve made every effort to acknowledge creators and secure permissions where possible. If you notice anything that may unintentionally breach copyright, please let us know and we’ll gladly review and remove any item of concern.

Index

- Australian Square Dance Publications

- Australian Callers Federation

- History of Convention Badges and Year Pins

- Square Dance Club History

- Square Dancing Youth Council

- How It Once Was

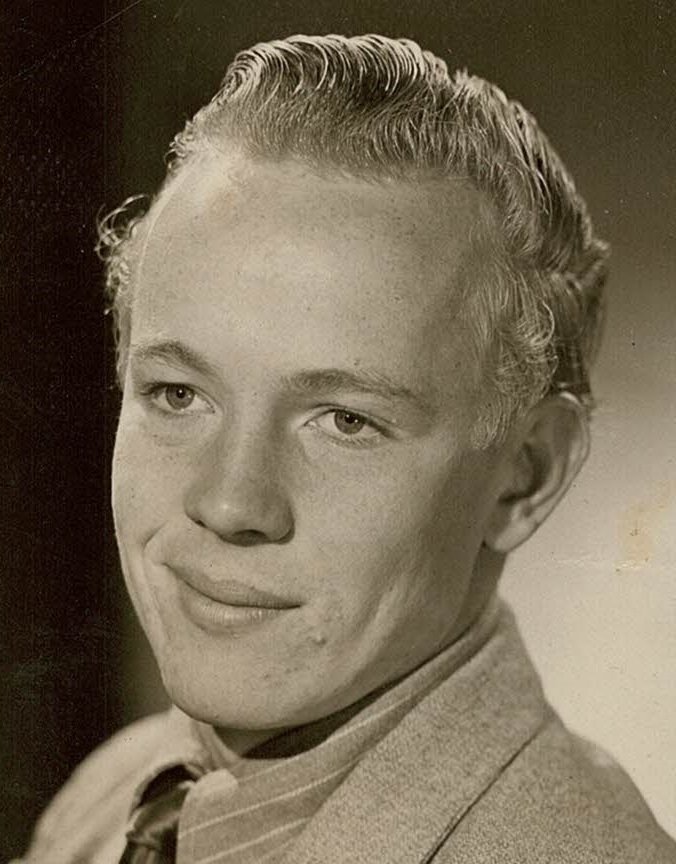

- Andy Lowan - New South Wales

- Brian Hotchkies

- Great Australian Callers by Graham Rigby

- Graham Rigby - Queensland

- Jim Vickers-Willis - Victoria

- Jim White - New South Wales

- Frank Kennedy - Victoria

- Tedda Brooks - New South Wales

- Frank Lambert - Rockhampton

- Square Dancing As A Sport

- How It Started In Australia by Jack Murphy

- Wilma Flannery - New South Wales

Square Dancing Youth Council

Now in recess

How it once was

A Brief History of Square Dancing

Reprinted from the old dosado.com website

Square dancing is an American institution and dates back to the 17th century when the first settlers moved from Europe to New England. The immigrants brought their national dances such as schottische, the quadrille, jigs and reels and as the nationalities mixed so did the dances. As the dances got more complicated it became increasingly difficult for the average person to remember all of the moves and the more able, extrovert, dancers took the lead and were able to prompt the other dancers. These extroverts were also able to learn the dances of other communities and call them to their own group. Many of them developed their own routines for four couples and American Square Dancing was born.

As the communities spread southwards and westwards so did square dancing but as the population became urbanised the influence of people from other continents had an effect on fashion, music and dances. This development caused square dancing to only be popular in certain regions and, as there was no central body controlling the development of the dances, the differences in the regions eventually meant that dancers from one region could not dance in other regions.

Square Dancing

In the 1930’s Henry Ford became interested in the revival of square dancing and his efforts motivated other individuals to modernise the activity so that it would appeal to a wide range of people. Square dance groups began to spring up all over America and by the late 1940’s people, who had rediscovered it, were determined to retain it and share it with others. Square dancing had regained its old appeal in a modern setting, initially spreading all over America but soon being exported to other countries, such as England, Germany and Australia, as Americans traveled with their work etc.

Square dancing is now very well organised and new moves are added every year to try to retain everyone’s interest and to develop the activity. There are different levels of dancing, Basic and Mainstream are the starting levels while Plus, Advanced and Challenge are for those who want to further their dancing repertoire.

Australian Square Dance Publications

For information on Australian Square Dance Publications

Please Click Here

As recalled by Jeff Seidel

(South Australia 2008)

The ACF was officially created back on the 23rd September 1979, in Adelaide. Going back a little further in time, Wally Cook, Jack Murphy & myself were on tour in North Queensland. Over the odd meat pies & liquid refreshment we discussed the topic of caller programming & ways & means on how things could be improved for the betterment of square dancing & dancers in Australia.

A list of callers was drawn up, noting what callers had been doing for the movement in their state & nationally, together with their ability to call. A short list of two callers from each state was chosen, except for Victoria, which at that time had two factions. The two factions had to be considered, in an effort to bring together the callers of that state, and consequently five callers from Victoria joined the ACF Board.

South Australia was to host the 21st National Convention in Adelaide in 1980. This was an opportune time to present this newly formed callers body to the rest of the callers and to the general dancers. So back to the 23rd September 1979, Jeff Seidel (also convener of the 21st) took this opportunity to send out invitations (in the same way Callerlab was formed in the USA) to a select group of Australian callers to join this new body. The callers were as follows (including state):

President: Jeff Seidel (SA)

Vice President: Tom McGrath* (NSW)

Secretary/Treasurer: Don Muldowney* (SA)

Ron Jones (NSW), Eric Wendell* (Qld), Graham Rigby (Qld), Les Johnson* (WA), Steve Turner (WA), Fred Burn* (TAS), Graeme Whiteley (TAS), David Hooper (Vic), Ron Whyte* (Vic), Ron Mennie (Vic), Jack Murphy (Vic), Wally Cook* (Vic), Allan Frost* (SA). Note: deceased members noted with *

All original members were made “Life Members”.

The name “Australian Callers Federation” or as known the ACF was the suggestion of Ron Jones (NSW). In its early years meetings were held twice a year, one at the National Convention & one about half way between the next. At this second meeting a fund raiser dance was also held. The ACF also started its own newsletter (note service) then called “News & Notes” – later renamed “Caller Link”. Steve Turner was our very first editor of this service.

I have been a Board member of the Australian Callers Federation since its inception in 1979.

Great Australian Square Dance Callers

by Graham Rigby

Jim Vickers-Willis.

Graham Rigby summed up Jim’s square dance calling career in Chapter 1 of his historical book titled “Great Australian Square Dance Callers – Over Half a Century” (ISBN 0-646-44628-2).

This extract from his book is reprinted with Graham’s kind permission

..….the “”Kings” of this era, drawing large crowds over the test of time, were just six, they being Eddie Carol, Jim Vickers-Willis, Bill McGrath, Wally Cook, Jack Murphy and Les Schroeder…….Jim Vickers-Willis, the unbelievably popular young journalist who, literally “took Melbourne by storm!” In early 1952, Jim and his wife, Beth, became involved in a charity square dance for their new Brighton “kindy” with Bill McGrath calling, and Bill being unavailable for their next dance (guess what?) the mike fell to Jim, who, with admirable humility, rose to the occasion. Enjoying it all, and learning to dance at Bill’s “Brighton” club,

Jim practiced hard at his calling and attracted five hundred dancers to their next church fund-raiser, and, soon after, the “Melbourne Sun,’ the newspaper for whom he [Jim] worked, produced a centre-page feature, resulting in his first group, the “Melbourne Square Dance Club’. Interest was spreading by leaps and bounds, and, by mid 1952, new clubs were opening most weeks, and, with major ballrooms becoming involved, Jim was engaged, in September, to call at “Earls Court’ St Kilda, and, for a short time at “Leggetts”. The one hour live radio broadcasts on 3DB from “Earl’s Court” on Saturday nights made numbers soar, and, with massive media build-up, Jim was, all at once, calling almost nightly to thousands.

By now, Adelaide beckoned and he responded on Monday nights, and in pelting rain at the “Palais Royale” opening, the huge crowd, nevertheless, jammed the entrances, overflowed the hall and overloaded the trams. Two weeks later, the dance was transferred to the huge Centennial Hall at Wayville, and, in this great “barn” four thousand dancers were taught each week. Coca-Cola trucks drove to the four corners of the hall, and, after a few short breaks, stocks vanished. Jim’s first (and only) “Roundup” took nearly an hour, so, from there on, it was “Square-ups” – such was the enormity of our activity at this time! Back in Melbourne, he was training callers (like Geoff Webb) who collectively operated about one hundred and fifty clubs all over the metropolitan area and Jim also had a “Bureau’; providing callers for charity shows without charge.

By early 1953, square dancing had become a multi-million pound industry, with sales of clothing in particular “going through the roof”.

Numbers continued to soar, until there were hundreds of thousands square dancing each week, and, on one occasion, Jim called for eight thousand dancers outside Melbourne’s Parliament House.

Recording studios, hesitant at first, suddenly got on the “bandwagon”, discovering that about half of their sales across Australia were square dance records, and, when Jim called for the “Sun Cup Final” at Melbourne Town Hall, three and a half thousand tickets were pre-sold in about forty minutes. Working sixteen hours a day, seven days a week, Jim had eleven weekly radio programmes nationally, and this boyish, friendly-voiced, thirty-five year old ex-spitfire pilot was at the centre of the world’s biggest “square dance boom” ever.

All at once, Jim’s “bubble burst; when, returning from Adelaide in 1954, he contracted polio and was rushed to Fairfield Hospital, with his legions of dancers rallying to provide an iron lung in his own home. During his convalescence, some even repainted the home and kept the garden immaculate, and Jim’s recovery was such, that, a year later, he returned to “Leggetts” for a hero’s welcome, with Eddie Carol and Graham Kennedy among the three thousand who attended.

In July, he and his wife, Beth, “the mighty atom” were off to Caloundra, on Queensland’s Sunshine Coast, where five hundred dancers and callers packed the Glideway Hall to celebrate Jim’s birthday, and, after four months of rest and resuscitation, they returned to Melbourne to resume their lives.

Is this story not worthy of a movie? We believe so!

Reprinted from the Jim Vickers Willis website

This information was supplied by his family

For further information, please click on the heading or photo

Square Dancing As A Sport

Reprinted from “People Magazine”

Vol 4. No. 11. July 29, 1953

A young man found a goldmine by giving a new twist to an age-old pastime. His name is Jim Vickers-Willis.

If ever an Australian film producer decides to turn out a colossal, scintillating, Technicolor, musical extravaganza of the struggling bright boy soars to fame variety, he has an ideal subject on tap, guaranteed to produce a tear in the eye, a pang of joy in the heart and rhythm in the feet Melbourne square-dance caller Jim Vickers-Willis.

A year earlier he was a worried young man with a very sick bank balance, Today, he wears a happy smile that isn’t false anymore, drives a shiny luxury car, and collects a hefty weekly roll.

He had a hunch that paid off. Largely because of his imagination, initiative and drive, the craze for square dancing has swept through southern States at a whirlwind pace since the end of 1952. Now, there are tens of thousands of registered square dancers in Victoria alone and rapidly snowballing thousands of devotees in neighbouring

South Australia. Vickers-Willis and his promoter John Brennan plan next to swoop on Brisbane and then the so-far-resisting Sydney.

For six nights a week, lean, likeable, sensitive-featured Vickers-Willis calls from the stage of Earl’s Court, St. Kilda to crowds of 2000 and more, then drives to his suburban home in Dendy St., Brighton, anything up to £180 the richer.

Ten thousand flock to the bayside dance hall every week crowding happily on to the four floors.

Some nights the doors have been closed in the face of queues that have stretched six and eight deep along the footpath, over the road, into a nearby park. Before Vickers-Willis began to sing into the microphones that carry his calls across the main dance hall and to radio listeners, a few hundred enthusiasts danced one night a week in one

section of the hall.

Today, more than 200 clubs are scattered throughout Melbourne, in several large ballrooms where the big time callers hold sway, in church and public halls where their dozens of trainees and lesser lights call to the ccompaniment of phonograph records and in private homes where amateurs try their skill.

Vickers-Willis has faith in the future of the entertainment that has put him on top of the world. Square-dancing has by no means reached its peak, he told a friend recently. I believe it will become five or even 10 times more popular than it is now. Its critics and even some callers themselves, say it’s a fad that will soon die. But why

should it? There’s no fear of tennis or golf dying.

Before the present boom, square-dancing was thought to be as dead as a dodo. It had been tried and it had failed, in several capital cities after introduction by American caller Joe Lewis a few years ago. It just didn”t catch on. Pockets of enthusiasts remained, but they were few and far between. Melbourne had one caller, Bill McGrath, who ran a small club in the upper-crust suburb of Toorak.

By chance, Vickers-Willis went to a local charity dance at Brighton where McGrath was calling, early last year. He was a journalist, a shipping reporter on the Melbourne Sun. During the war, as a RAAF pilot instructor in Canada, he had seen square dancing on its home ground when he took jaunts across the border into the USA.

This night, at Brighton, he entered into the fun. He enjoyed himself and so did everyone else. The dancing was appealing, the music catchy and the costumes colorful.

He found where the faults lay.

As the evening progressed his mind started to work in analytical circles, the gift of which is part of his stock in trade. He thought, There’s something in this. It appeals. It has possibilities. But something’s wrong. Why hasn’t it caught on?

Months later Vickers-Willis was still thinking. He had become a square-dance fan. Gradually he found out where the faults lay. He decided what square-dancing had to offer, and what the Australian public wanted then dovetailed the two together.

He evolved a form of square-dancing unique in the world, which he has described as being as far in advance of the American hillbilly style as baseball is in advance of rounders. He turned it into a sport.

Vickers-Willis based his reforms on three points, competition, synchronisation of call, music and step; and dress.

The competitive element has been in square-dancing all the time but it has been ignored, he says. Before, there was an endless variety of rules, and all of them said, generally you do so-and-so. But to my mind there should be no generally about it. In a game of cricket you don”t say, If a batsman’s caught, hes out and next time you play, decide to count only those clean-bowled.

I have established a rigid set of rules, through which the dancers pit their skill against the caller. He calls the steps,

deliberately trying to trick them. As the sets falter they are eliminated until the last is declared he winner. His form of dancing appeals strongly to the Australian sporting instinct.

Vickers-Willis developed the competitive angle in the impromptu dance (The other form is the singing dance which has a set tune and pattern).

In the past the caller called, the band played and the dancers danced, all to their own time (In many cases this still happens). But it grated on Vickers-Willis, until he found a way to overcome it. He fitted his impromptu calls to several basic melodies and trained a band to improvise accompaniments that kept time with him and the sets.

John Brennan and I set about cutting out the hillbilly stuff, he says. Earl’s Court announced that no square dancers would be admitted in jeans previously the standard dress for men.

We considered cowboy boots, jeans and flashy shirts frightened off more men than enough. Now men wear what they would during an evening at home, sports trousers, golf shoes and bright shirts and scarves if they wish.

The women wear colorful skirts and blouses. Pseudo Yankee accents also went by the board. (He has almost an English accent himself). The dancers must hear calls clearly.

By a stroke of fate, tragedy is responsible for making so many people happy. Few of the thousands who dance and laugh in the hall of Earl’s Court are aware that the tall, smiling young man who leads them through the ntricate steps has been spurred on by unhappiness.

His two bonny children, Suellen 4 ½, and Peter 2, were born with double hair lips and cleft palates. Medical science said that such an event was all but impossible. But the near-impossible happened.

Sensitive, loving Vickers-Willis was heartbroken, but he didn’t throw in the towel. He set to work to make money for plastic surgery operations that have cost him hundreds of pounds. He says, I’d never have been in square-dancing if it hadn’t been for the kids, bless their hearts. His wife and he are overjoyed that the operations are working

miracles.

Vickers-Willis was born in England 34 years ago and came to Melbourne with his parents as a child. After a grammar school education he became a reporter on the Sun.

He joined the RAAF in 1940 and spent 6½ years in the service, most of that period in Canada and the Islands.

Vital, loose-limbed Vickers-Willis, who at a glance could be mistaken for an American, returned to Australia with a lot of money-making ideas he had picked up in the US. He resumed work as a reporter, but at the same time sank his deferred pay into a project to set up a chain of mobile canteens to cater for bathers at bayside resorts. He called then Thirst Aid Posts.

He laughs about the early experiment now. The idea was good, he says, But I was undercapitalised. I bought two caravans, an old truck to tow them and a mobile canteen. The truck was always breaking down. One night still sticks in my mind. It was straight from a Laurel and Hardy act. I was towing one of the caravans home when it became unhitched. Over my shoulder I saw it heading straight for a jeweller’s window but it hit the high gutter and stopped. Bottles, ice cream and sweets went everywhere. I reversed the truck, hitched up the caravan, jumped aboard, and slammed the door. Then the horn jammed and blew on top note. I hopped out, fiddled with it and it stopped. By this time quite a crowd had gathered. I dived into the cabin and slammed the door so hard the other one flew open and the horn started blowing again.

Was my face red by the time I got out of the mixup?

When Suellen was born, Vickers-Willis got two years absence from his paper and opened his Thirst Aid Posts on Port Melbourne’s piers to cater for persons awaiting the arrival of overseas ships. He made the money necessary for his daughter’s operations then went back to journalism.

When Peter was born also with a double hair lip I knew I,d have to go through the hoops again and I was ready to go back to the business (he hates to be called a piestall proprietor) when by chance I went to a charity square-dance, he recalled recently.

Immediately I saw the possibilities. The months that followed convinced Vickers-Willis that he was on to something good. He began to tackle the calling.

After small dances he held in local halls, a crowd of friends would return to his home and carry on until all hours of the morning. He was impressed by the fact that even those who were considered good hard drinkers would refuse an offered thirst quencher with, No thanks, Jimmy. I’ll have one later. (He says, You need a clear head and concentration for square-dancing so drink is taboo, and seldom missed, in all clubs.)

When Vickers-Willis bought a microphone and pickup and began practicing calling far into the night, his attractive black-haired dark-eyed, young wife, Beth, muttered in despair, You’re going bats! and went to bed. But his keen business mind had seen a way of earning money necessary for the doctor’s bills yet to come.

He set out to create public interest.

There is little doubt that he was behind the square-dance charity ball in July, last year, for which the benefiting charity workers and their children buttonholed 500 people into buying tickets. Vickers-Willis calls this the turning point in his life. I know that the majority of the crowd weren’t a scrap interested in square-dancing, he admitted

later, but once they had paid their money they were determined to get something for it. They all turned up.

At first it looked like being a classic flop. The microphone went bung and most were beginners who didn’t care whether they danced or not.

In desperation I started the Alabama Jubilee, which was a popular record at the time, with my own variations. It

caught on, and the crowd went mad. With the ball rolling, the night developed into a tremendous success. The Alabama Jubilee is now my theme song, and I’ll wear the shirt and scarf I wore that night until they are threadbare. I believe they brought me luck.

The almost hijacked patrons of the charity ball fell under the spell of square-dancing and became the nucleus of the 464-strong Melbourne Square-dance Club which Vickers-Willis formed to consolidate his newly-won ground. He also followed up with feature newspaper articles which aroused attention, and snatched at every possible scrap of publicity offered.

Cinderella square-dancing began to shed her tattered clothes. Almost overnight clubs sprang up in Melbourne suburbs, some established by Vickers-Willis and others by Bill McGrath. The snowball had started rolling. Then the big chance came for Vickers-Willis. He got a telephone call from radio 3DB’s manager, asking if he was interested in calling for the broadcast dance at Earl’s Court? He certainly was.

He knew that the program that had been on the air for the previous few weeks had not hit the spot, and that he could give the crowd and the sponsors what they wanted.

The audition that followed no doubt would be the griping climax of that proposed musical move. Vickers-Willis went along to Earl’s Court that mid-week night with proprietor John Brennan and 3DB manager David Worrall and listened to the other hopeful contender for the contract call to imaginary sets, the monotonous chant echoing around the empty hall.

Then, as Vickers-Willis prepared to take the stage, scores of laughing, coluorfully dressed dancers who had been waiting in the darkness of the foyer poured on to the floor and took their places in their sets of eight. His trained band formed behind him and as they struck up he called for his friends of the Melbourne Square-dance Club

who had turned up in force to back him up in the break of a lifetime. The dances ended with bursts of applause and cheers an atmosphere to gladden any promoter’s heart. Later, the crowd waited as executives conferred.

The minutes dragged by, then they announced, You’re on next Saturday night.Vickers-Willis immediately started beginners classes and 68 people turned up the first night, 150 the next, and within weeks square-dancing had taken over the four halls of Earl’s Court.

Since then, the snowball has rolled down hill. In December, he formed the National Square-dance Club and the Square-dance Bureau which handles bookings for dozens of callers he has trained. In January, he left his journalist’s job, finding his income from £100 to £180 a night, six nights a week, quite enough to live on. He has a radio program, writes a weekly newspaper column, is preparing what he claims will be the book on square-dancing (he has written five unpublished novels) and is managingdirector of his two small Thirst Aid companies. His wife, long ago convinced that he wasn’t going bats after all, works with him and is a member of his exhibition set.

Vickers-Willis, of course, is not the only ace caller in the field. There are others who claim to be a bigger noise than he. But he doesnt a’rgue. As long as they are developing interest in square-dancing he is happy. He has a following of staunch supporters who like his work and admire him personally.

The square-dance enthusiasts are not all youngsters. People of all classes and ages have vaulted into the ommon melting pot. Doctors, lawyers, and other professional men are seen every night cavorting with a zest they haven t displayed since they left university or college.

Teenager youths sashay around the middle aged partners and clasp 40in waists in swirls as enthusiastically as if they were 20. Some fans don their casual gay clothes to promenade and do se do two and three nights a week.

In the final scene of this motion picture that probably will never be, the camera would undoubtedly pan down on the smiling Jimmy, and then move back and fade on the family scene of the man who has made the grade, his wife and his children, leaving the audience to utter mentally that old blessing, and they lived happily ever after.

Square Dancing - How it all started in Australia

as viewed by Jack Murphy (Victoria)

Jack Murphy a Melbourne Caller in the 1950’s who developed his skills through the McGrath square dance camp.

Jack had great longevity – surviving more than 50 years in square dancing.

American servicemen took square dancing to England where it is very popular today and also with the occupational forces at the end of the war to Japan. Two events led directly to the growth of square dancing in Australia. One was the return from Japan of two girls who had been teaching soldier’s children and who had been introduced to square dancing by American servicemen. The other was the visits of Dallas, Texas, caller Joe Lewis.

Several small groups had been square dancing before these events took place, mainly with a small repertoire of singing calls. In New South Wales Eddie Carol had been trying to popularise square dancing ever since he learnt to call as a young lad, with little success and much opposition from dance promoters. An American caller named Leonard Hurst here with the American services during the war, led American servicemen and local girls through their paces at the Red Cross Recreational Centre in Townsville, Queensland, while he was stationed there. He later married an Australian and made Adelaide his home. These were only isolated events.

The growth of square dancing in Australia really dates from the first two events mentioned.

The first event took place at the Teachers’ College summer camp at Queenscliff, Victoria, in 1949. The two girls back from Japan were attending the camp and they passed on the knowledge of square dancing that they had learnt there. Also at the camp was Bill McGrath, a lecturer in physical education. Square dancing interested him right from the start and he began learning all he could about it. From then on it became a regular activity at the Melbourne Teachers’ College, and Bill McGrath set out to interest other people.

In March 1950, the Teachers’ College held a square dance in Melba Hall, at Melbourne University, attended by over 400. Many other demonstrations were given throughout Victoria in 1950 by Bill McGrath’s exhibition sets, and over 6,000 people went to the Melbourne Town Hall to see a “Hollywood Square Dance Contest”. Square dancing in Victoria became very competitive and the Victorian Championships were held that year in Prahran Town Hall. Twenty-two sets were entered and all three places were taken by sets trained by Bill McGrath. On the whole, 1950 was a year of struggling to interest people in Victoria without much success.

But at the end of the year an event took place in 1950 which was to lead to the forming of Melbourne’s first square dance club. During the Christmas holidays a group of people with homes on the Ranelagh Estate bought a set of Joe Lewis’ records and got together to work out the cells and dance to them.

Joe Lewis’ first visit to Australia also took place in 1950, when he gave exhibition to big crowds in Sydney. This led to a boom in square dancing in Sydney for a while, but it soon died, due to a lack of suitable callers and the fact that some of them made a farce of the dancing and dressing,

It was the second visit of Joe Lewis in 1951 to conduct the “Women’s Weekly” 6,000 pounds competition that gave square dancing its big and much needed boost. In conjunction with the Australian Championship, Joe Lewis called for many exhibitions at leading stores in both Melbourne and Sydney, and brought square dancing to the notice of a big section of the public

Eddie Carol was the official caller for the Australian Championship which was won by the “Denver Dudes” of Sydney. Members of the set were: Gary Cohen, Roy Starkey, Colin Lister, Sydney Tomlin, Pat Cohen, Marie Weston, Shirley Clifford and Ivy Newman. A Victorian set was second. Joe Lewis was the judge.

Local callers, Eddie Carol and Bill McGrath in particular, were also able to gain much valuable experience from Joe Lewis. Joe left behind a band of well trained dancers, many of whom later became callers.

Now let’s get back to the group of people at Ranelagh Estate who taught themselves to dance from records. When the big competition was announced they decided to enter a set in the Victorian section. They had caller Charles Leesing to train them, and danced so well that they reached the final round. After the competition they decided to form themselves into a club, and so Melbourne’s first club, the Village Square Dance Club, at Toorak came into being. Charles Leesing continued to call for them for a while, then Bill McGrath took over, and by the end of 1951 the club had closed its membership.

In Sydney after the competition, Eddie Carol was selected to call at the Trocadero, one of Sydney’s biggest ballrooms, and many clubs sprang up.

The stage was then set for the square dancing boom to begin. The Village Club had closed its membership and was rapidly reaching an advanced standard of dancing. To cater for the overflow of dancers another club was opened at Brighton early in 1952. The craze was spreading, and by the middle of 1952 new clubs were forming almost every week. T and Whitehorse are still operating today . Some clubs were banded together under the Square Dancing Society of Victoria, and Bill McGrath had begun training a team of callers to take over the new clubs as they opened.

By this time the big ballrooms were beginning to sit up and take notice. They soon realised that square dancing had taken a good hold and that ballroom dancing must suffer as a result.

In September 1952 Earl’s Court, St. Kilda, opened for square dancing, and Leggett’s, Prahran, followed suit. A young Melbourne journalist, Jim Vickers-Willis, who had been dancing with the Brighton club, began calling at both ballrooms. As an experiment a broadcast was made from the Earl’s Court dance, and it proved an immediate success. This broadcast and the many others that followed did much to bring square dancing to everybody’s notice, and the boom was then really under way. By the end of 1952 the Square Dancing Society had over 100 clubs and more callers were being trained.

In Sydney square dancing had once again left the big halls, but was still going strong in a number of small clubs. It was about this period that some present day callers namely Wally Cook (Vic), Jack Murphy (Vic), Ron Jones (NSW), Les Johnson (W.A.), Kevin Leydon (Vic) and Lee McFadyean (Vic) commenced their calling careers followed by Graeme Rigby (Qld) and Graeme Whiteley (Tas) in 1953 and Allan Frost (S.A) in 1954.

Eddie Carol with his wide experience and knowledge soon became a firm favorite with Melbourne square dancers. He brought with him many new ideas and dances, which he passed on to Melbourne callers, and Leggett’s soon had to increase its square dances to five nights a week. Early in 1953 Cr. and Mrs. McIntyre, Mayor and Mayoress of Box Hill decided to give a Mayoral Square Dance Ball – Australia’s first with Jack Murphy as the caller. All the guests were square dances and they bowed to the Mayoral couple in true square dance style. The Whitehorse presentation set after making their bows gave an exhibition.

New South Wales:

In the early fifties square dancing staged a revival in Sydney with the formation of the Australian National Square Dance Club, which had opened beginners’ nights in several suburban ballrooms and town halls. Two of the early established Sydney clubs were the Carrs Park and Balgowlah clubs. The Carrs Park club was restricted to married couples only. Prominent callers in Sydney at the time were: Ron Jones, Gary (Chuck) Cohen, Smiling Billy Blinkhorn, Alan Blackwell, Jack De-La-Warr and Erin O’Daly.

South Australia:

Adelaide’s first club was launched by American caller Leonard Hurst in 1951 at the T.W.C.A. known as the “Sundowners” which became a training ground for future callers. Len Peters was to become the first local caller. For a while Jim Vickers-Willis flew weekly from Melbourne to call at the Palais Royal and Graham Stone also called there as well as at the Embassy.

Western Australia:

Square dancing in Perth started in 1953 and was restricted to a few small groups, meeting at irregular intervals. The first clubs to form were Milsurf in Subiaco with caller Ross Ewen who was a lecturer in Physical Education at the Teachers College and Circle “C” with caller Laurie Nash, also a club named Orano. Square Dancing was given a boost in 1954 when a dancer named Fred Humphries who was a starter at the 1956 Olympic Games, invited Bill McGrath and Jack Murphy and his Whitehorse Exhibition set to perform in Perth at such clubs as Milsurf, Circle “C”, Mt Lawley & Bunbury.

Queensland:

Square dancing also came to Brisbane in 1953 but was confined to, small groups, until the arrival of Melbourne callers Bernie Kennedy and Doug Neeson. Clubs then opened very quickly with local callers John Gurney, Harvey Lake, Ray Ryan and Graham Rigby.

Tasmania:

In Hobart, square dancing commenced in 1953 at Charlie Brown’s with headquarters in the Royale Ballroom with caller Freddy Goninon. Brown and Goninon virtually pioneered square dancing in Hobart. Apart from Goninon there was a caller named Peter Smith who conducted his own club. Peter had been calling for sometime as he started back in his homeland – England. In 1953 Launceston boasted as many as 22 clubs. The Northern clubs formed an association and in conjunction with Radio 7EX and the National Fitness Council conducted Tasmania’s first Square Dance Festival at Campbell Town. Graeme Whiteley also started his calling career about this time.

TEDDA BROOKS

TEDDA BROOKS 1933 – 2025 New South Wales

With great sadness we learned that our great friend Tedda Brooks passed away on 15th October 2025, aged 92.

Tedda is survived by his wife Marion, his four daughters Diane, Sharon, Janelle and Julie, and his many grandchildren and great grandchildren.

He was one of life’s true gentlemen, always ready with a smile and a friendly word. He will be sorely missed.

Many people will remember Tedda as a wonderful caller and entertainer who brought much happiness to hundreds of square dancers at the Guys and Dolls Square Dance Club.

He and his first wife Hazel were introduced to Square Dancing by friends in 1981, tentatively entering the crowded square dance floor at Knee Deep Squares. Always a showman, Tedda soon began guest calling, and it was not long after that “Guys and Dolls” was born, and a star was born.

There were many highlights in Tedda’s calling career, including calling to many squares on the steps of the Sydney Opera House, featured at the Premier’s Seniors Concerts, and calling on luxury cruise ships.

After Hazel passed away in 1993, Tedda devoted his considerable talents to raising thousands of dollars for the Calvary Hospital in Kogarah, where there is a ward named “Guys and Dolls”. After he and Marion were married, they relocated to the Wollongong area where he continued calling into his late 80’s, until he and Marion moved back to the Sutherland Shire.

In 2017 Tedda became a recording artist on the Knee Deep Melodies label, releasing “It had to be you” and “Bye-bye, baby, goodbye.” His wonderful talent and personality shine through on these great recordings.

Rest in peace, Tedda. We love you, and you will be sorely missed.